Art for all. And all for art.

Art for all. And all for art.

The call for representation in art is louder than ever before. Here, we hear from CCAD grads and family who are on the forefront of making sure that marginalized voices can be heard.

Continue reading below...

Enter a Google search for “most famous artists” and you’ll find a familiar sight.

The result bar’s first 40 photos and names showcase only two women (Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe) and only one African-American (Jean-Michel Basquiat).

Then there are the numbers. In ArtNet News’ list of the top 100 individual works sold between 2011 and 2016, only two were by women artists. Of those 100 artworks, 75 came from the same five male artists.

Evidence of the art and design world’s lack of diversity abounds in the work itself, too, with expressions of the same class, gender, color, or experience showing up over and over again.

That’s all about to change.

“The voices of underrepresented populations—people of color, women, LGBTQ communities, have been undoubtedly marginalized, if not omitted from the narratives throughout the history of art,” says Aaron Petten, assistant professor of History of Art & Visual Culture.

“What’s exciting about the present is that we’re in the midst of a revolution where it seems that a very wide range of voices are being seen and heard in the art world...the achievements and stories of the marginalized voices of art history are being incorporated more regularly as part of the central fabric of the story that is art’s history.”

“The voices of underrepresented populations—people of color, women, LGBTQ communities, have been undoubtedly marginalized."

—Aaron Petten

Certainly there have been efforts to course correct visual culture’s underrepresentation for some time. Consider the decades-long feminist skewering of ivory tower art institutions by the Guerrilla Girls or the LGBTQ resistance pushed forth by seminal collectives such as fierce pussy.

But, in 2018, the demand for representation in art—and everywhere else for that matter—is stronger and more influential than ever. From stages as big as Netflix (comedian Hannah Gadsby’s special Nanette practically rewrites the history of art and its idolatry) to the personal such as on CCAD’s campus (we’re so here for the work of The Black Infinity, a Columbus-based community whose members, many CCAD alumni, mobilize support and opportunities for underrepresented artists and designers).

“I think CCAD is taking a more active role in ensuring that [representation] is something they’re always evaluating,” says The Black Infinity founder Tosha Stimage (Fine Arts, 2011), who also serves as Fine Arts Visiting Faculty with the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design.

“Acknowledgment of other people makes students feel safe. And I think students feeling safe is key. If kids feel safe, it opens them up to learn even more.” In her individual practice, Stimage explores how language impacts the way we see each other—or don’t. Representation is the key to unlocking room for every voice.

“The idea is that, in the shared space of society, if everyone is able to engage and throw things into the pot we can challenge each other and figure out solutions,” she says. “We can imagine these possible futures with art. Artists have this uncanny ability to create language that’s very future thinking.”

Indeed, art and design’s blind spot is the same one every sphere of society has been called to witness, finally, but art and design students are particularly primed to do more than just see it.

“We’re recovering from centuries of oppression,” says Fine Arts Associate Professor Danielle Julian Norton. “How do you recover from something like that without constantly trying to implement representation and give everyone a seat at the table?”

In her classes, as well as her individual practice of creative agriculture, Julian Norton encourages open discussion and critique of contemporary culture and works alongside students to figure out how they can use art and design to change the status quo.

“Through these conversations we can evaluate ideals that might compromise equality,” Julian Norton says. “Artists have always been tuned in to forecasting progress.”

“Artists have always been tuned in to forecasting progress.”

—Danielle Julian Norton

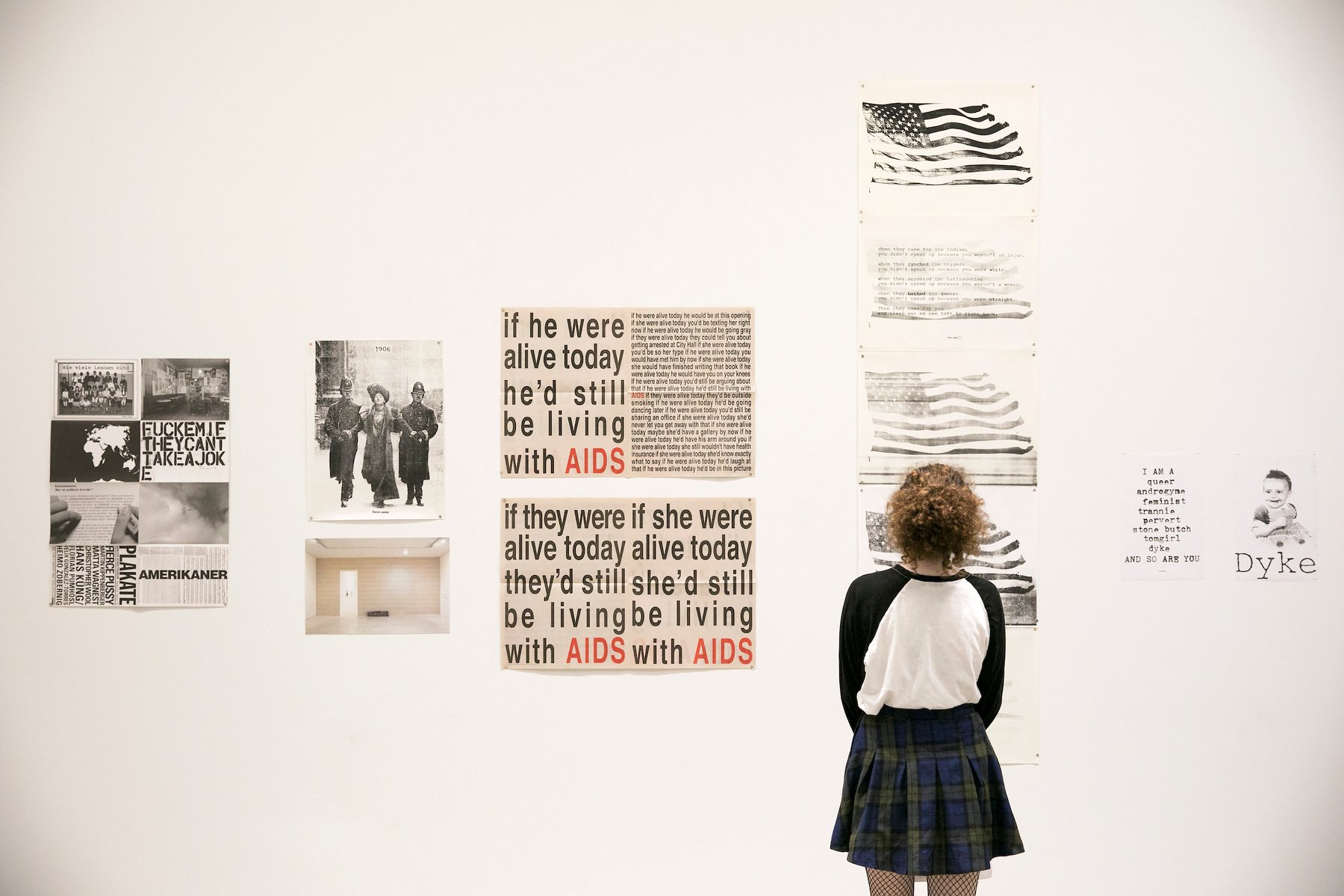

Joy Episalla's work in Chapter One

Queer art history (continued):

“It is a beautiful and inspiring archive of a group of women who took charge of change and educating the public,” says Janelle Bounfour-Mikes (MFA, 2020). “Women have a much lower rate of being shown in a gallery than men. Showing not only women, but feminist women, is incredibly important in the future of the art institution.”

A New York–based collective, fierce pussy formed in 1991 as a response to the AIDS epidemic, and its artists produced low-tech, high-impact artwork out of found media. Season One’s compilation of installations, performances, lectures, and more represents the first time direct inquiry has been made into the individual practices of fierce pussy’s founding artists (Nancy Brooks Brody, Joy Episalla, Zoe Leonard, and Carrie Yamaoka).

“Their grassroots approach is incredibly inspiring given the current political climate,” Bonfour-Mikes says. “[Nancy's] materials are also incredibly intriguing to me as a former dancer. The lead pieces are strong, but not rigid. They are pliable like a body. It reminds me to stay strong yet vulnerable in my body and my spirit.”

While the collective’s early text-based work served as a megaphone for cultural voices historically silenced,

Beeler’s consideration of each artist on their own terms establishes a meaningful evolution of how we see others in art.

“These artists have, for decades, sustained their own art practices while maintaining engagement in social activism. I find that balance critical in this moment we live in,” says Director of Exhibitions Jo-ey Tang. “It’s a reminder of the vital roles individuals occupy in the fabric of our social condition.”

Sheerleelah Jones taken by Darrell O'Neal

Sherleelah Jones

Owner and creative meditation instructor at Neon Alchemy, watercolorist, digital painter

Sherleelah Jones (Media Studies Time-Based, 2007) focused on filmmaking while a student at CCAD, but had a difficult time finding a space for herself in the world of film—on campus and off.

Continue reading below...

Creating safe spaces (continued):

“The lessons I learned about myself as an artist came from adversity and not feeling completely understood as a black female artist,” she says. “It was intimidating. There weren’t a lot of women of color creating content or making shows. It felt like I had to create my own way. It taught me I can self-motivate and that I can persevere.”

When she met Celia Peters, founder of Futures for the Rest of Us, a 2018 exhibition of futuristic work by artists belonging to groups traditionally not shown in science fiction, she found what she had been looking for as a student.

“Celia was filming an event I attended, and it was amazing to see a black woman behind a camera,” Jones says. “I have to meet and talk to this badass woman,” she thought.

Much of Jones’ professional and personal practice now revolve around making a safe space for herself and others to find themselves, too.

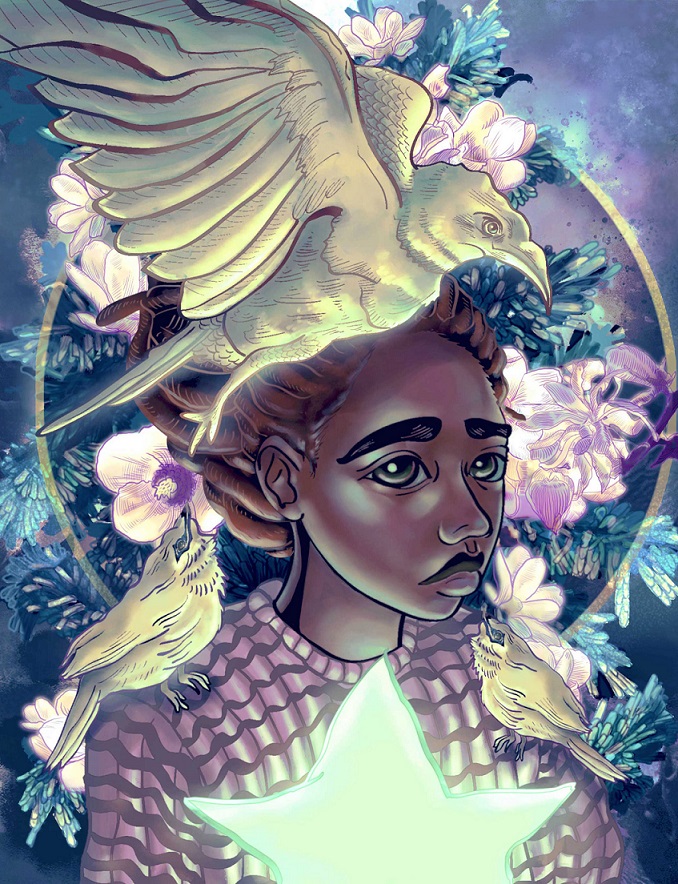

Kintaro Tale (2017), digital painting by Sheerleelah Jones

Lumina-Amethyst (2016), digital painting by Sheerleelah Jones

Why do you think it’s important to use art to challenge norms?

Being someone giving representation and voice is such a scary idea for me, but that’s why it’s important. I’m always trying to avoid the angry black woman stereotype. We have to be everything to everyone. Representation is how we help break that down. It’s why I loved watching Grace Jones play phenomenal women when I was a kid. Now there are the Avas, Mindys, Issa Raes, Shondas, Kara Walkers, these beautiful women creating content, making work, and representing women of color. It’s important to be seen.

The women I paint have dimension. That’s me giving myself the privilege of duality, instead of being what society intends me to be. But it’s also me giving myself a safe space where I don’t have to be this superhuman boss woman every day. I want to show the truth of identifying and discovering.

Umbra-Midnight (2016), digital painting by Sheerleelah Jones

What did you make for Futures for the Rest of Us?

My [watercolor painting’s] subjects were black women, and it was a very lyrical, surreal piece that had to do with how we would communicate in the future, empathically, through eye contact, symbols, light. The characters were weightless and among trees and nature. It alludes to getting back to our true selves without the interference of others—your higher self, your true self, the self that knows you when you doubt yourself. In the future, if we had the space to do that, feel safe to be ourselves, what could the world look like?

Corey Favor

Corey Favor

Associate art director of UI/digital design at The Ohio State University, co-founder of Creative Control Fest (CCF). When Corey Favor (Illustration, 2003) graduated CCAD, he knew he had a job to do: make the cultural experiences on campus better for others.

Continue reading below...

Leading the change (continued):

“I volunteered my time, provided resources for students, and worked with faculty and staff to improve the student experience,” he says. “Today's students have a lot of resources and support I didn't have during my time on campus.”

As a newly appointed member of the CCAD Board of Trustees, his efforts extend beyond campus, too. This year, Favor and Marshall Shorts (Industrial Design, 2006) present the seventh year of Creative Control Fest. The pair started the conference to unite creative professionals, Favor says, “ to foster a creative culture with self-perpetuating diversity and inclusion.”

The theme of this year’s CCF? Power.

Photos from Creative Control Fest taken by Ty Wright for CCAD

Photos from Creative Control Fest taken by Ty Wright for CCAD

Why power?

As individual creatives, we can do great things. But, as a collective, we can make real change. And that's powerful.

Why is representation especially important right now?

Representation has and always will be important. You can’t accurately depict the world without a variety of perspectives. Throughout history, art has always been a vehicle for change. Art is a powerful mechanism for change, community, and culture.

Photos from Creative Control Fest taken by Ty Wright for CCAD

Do you think Columbus is a good place to be an artist?

Columbus is a great place to be an artist. There is so much talent, energy, and opportunity. The Harlem Renaissance Project is a great example of some exciting creative work happening right now. It connects on so many levels and is a great example of education, social impact, and celebrating history.

Cameron Granger, photo taken by Nathan C Ward

Cameron Granger

Filmmaker, Artist in Residence at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts.

Cameron Granger (Cinematic Arts, 2016) credits his mom with showing him he could be an artist—even though he didn’t see a lot of people like him making art in the mainstream.

Continue reading below...

Forging the future (continued):

“My mom was really focused on bringing home books by black folks, movies by black folks, art made by black folks,” he says. “She was very consciously doing that at all times. Even if it wasn’t her saying I could do this, she was making me think I could.”

Fast forward to college, where the support of professors and alumni mentors helped solidify his pursuit to make films. Now, between artist residencies and freelance work for Columbus agencies, Granger participates in paying his experiences forward through his participation in The Black Infinity, whose members mobilize support and opportunities for underrepresented artists. He also finds a lot of inspiration from his social media communities.

“I like seeing humor online, which can make a horrible time that we live in easier to cope with,” Granger says. “There are so many dark things that talk about blackness, and I’m kind of over that.”

What does representation mean to your artistic practice?

I make work that is a way for me to look at the media I raised myself on in place of having a father figure, and to look at representations of black men and black boys that I molded myself around or after. Because I didn’t have something like that around me when I was little, I’m trying to see what my place is in the middle of all this. I’m a black male making media about black men and black boys.

What kind of change do you hope to see in terms of representation in the arts?

In a perfect world, my utopic view of when the battle for representation is over is when we won’t have to have these conversations. Work by black folks or folks of color, in the gallery space or on TV or in the movies would be as regular as white folks doing these things. We talk about “this black film,” “this black artist.” Can’t they just have the freedom to be an artist without having to subvert some kind of cannon or revolutionize something?

Why did you get involved with The Black Infinity?

The Black Infinity comes from a genuine belief in the power of art and what representation in art can do for a community. It activates a gallery space in a way we don’t see in a lot places. If it wasn’t for my mom telling me from the time I was little that I could make art, I wouldn’t be doing this. I didn’t see black people making art. If I can be that person for someone else and help them find their way, I think I should do that. I don’t think every artist of color should feel like they have to give something back—that’s an unfair responsibility to cast on someone—but I found myself making things because I had someone show me it was possible. I had so much help along my way and incredible mentors. I want to do that for someone else.

Post date

October 22, 2018